Pursuing platinum: an elementary philosophy

12 years ago, I walked into a new elementary school as a second grader. I had no friends and no plan to make new ones, so I naturally gravitated towards the empty baseball field and sat to play in the sand.

I would pile heaps of sand up, draw Zen-styled patterns, poorly attempt to create castles, and even spend days running the grains slowly through my hands.

Yeah, I know. It was a lonely first few weeks, though I guess I wasn’t completely alone. My attention was often caught by a curly haired boy, not too far away, concentrated on a unique operation: he showed up every recess and lunch to the baseball field, the same way I did, and began an excavation, furiously digging and inspecting the sand.

Eventually, curiosity overtook me. In an attempt to make a new friend, I walked over and inquired of his work. He took a good look at me and screamed a response:

“NONE OF YOUR BEESWAX”

Ah. The 2nd grade equivalent of f*** off.

My first attempt at friendship didn’t go so well. He was secretive, but I was still persistent. A week later we ended up becoming friends at an afterschool daycare. The boy, who introduced himself as Matthew, brought me in close and decided to reveal his secret.

Amongst the sand at our local elementary school, unknown to any other human but himself, was the highly precious metal, Platinum.

He then made me an offer that changed my life: “Do you want to help me?”

Naturally skeptical, I asked how he knew for sure. Using our trusty 2nd grade science book, he compared his current supply of dirty, black rocks with a rough, lookalike picture of platinum — coincidentally another dirty, black rock.

He presented a particularly strong case. I was in.

So, for the better part of second grade we spent our recesses and lunches harvesting the commodity. It was no easy task either. It’s quite literally like trying to find a needle in a haystack, except needles and hay shorten from two dimensional lines to one dimensional particles across the mass of grains. To find a single piece took a sharp eye and diligent digging.

It was only a matter of time before mutual friends broke our veil of secrecy. As soon as our mission was public, the mocking began. Amused teachers asked us for mansions after we sold our fortunes. We had to hide our collections from our parents, who thought the very idea was unhealthy. We didn’t care. We rebelled and pushed through the noise.

Across all of those months, we had accumulated pounds of the little rocks, separated into a variety of Zip-lock baggies (and more dirty pairs of jeans than we could count).

There’s perhaps a reason you haven’t already read this story from a Forbes magazine though. Eventually intellect + research caught up to us and we came to the heart-breaking reality of the rock being filler sand. We didn’t get insanely rich — our collection was nothing but debris. All that time and effort gone to waste.

Yet despite spending over 6 months collecting what was effectively blacker dirt, I still look back at the year and smile.

Though I’ve matured in both my scientific procedure and intellect, it’s important for me to maintain the curiosity of a second grader — to question my peers and surroundings with no fear of the results and all focus on the process.

Fearless Curiosity

Today, Matthew Sotoudeh is one of my best friends and partners across a slew of side projects, a startup, and a summer academy.

The moral of the platinum story is that you should live by a mantra to look at opportunities + problems around you, no matter how ridiculous, and pursue them. Curiosity can fuel you to answer questions that interest you, if you let it.

Now what I don’t mean to suggest is that we all start asking questions about everything in the universe. The world is a pretty large sandbox and there are a billion particles of sand to look at. Context is important and focusing on what already immediately surrounds you and your environment is the best place to start. Look at issues you’re already invested in and put forward ideas on how to fix them. If you can measure any form of utility, then continue along that vein.

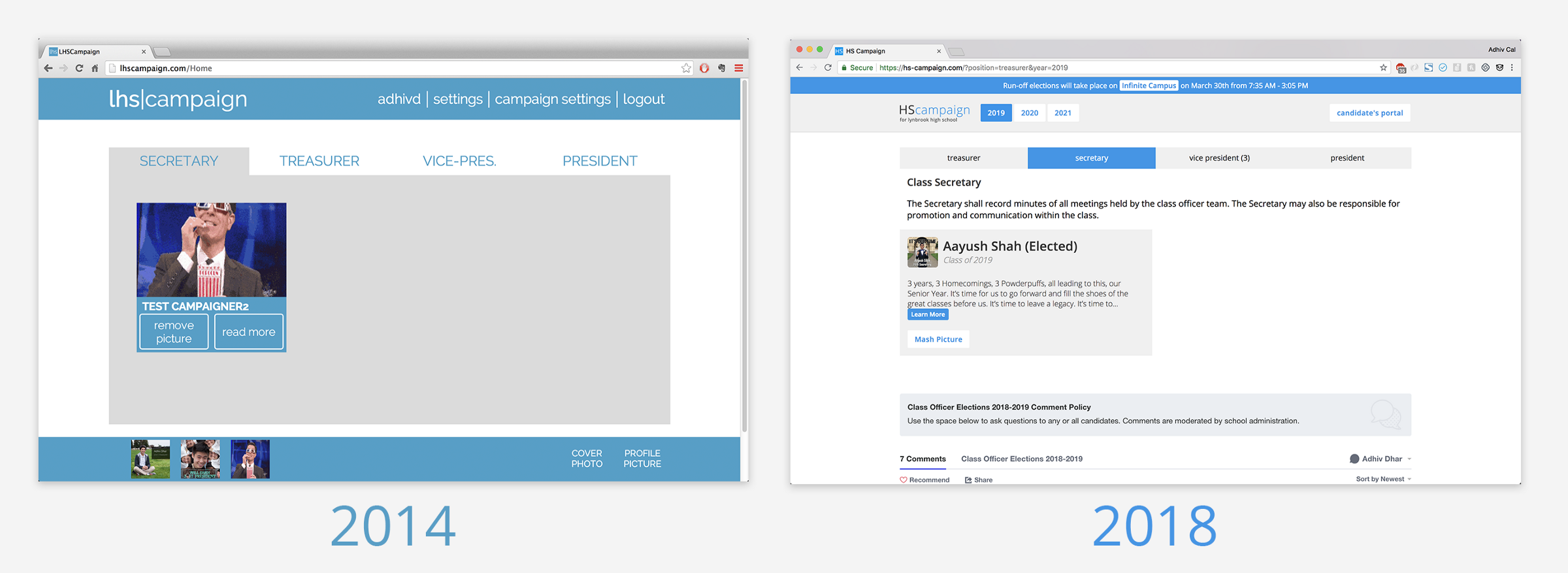

To put an example to it: Matthew, Will Shan, and I were all involved in student government, so naturally we were looking at problems surrounding that sector. When we first put out HS Campaign in our freshman year of high school, it existed merely as a tool for people to mash Facebook campaign photos together. It wasn’t too long after we put it out that we realized it could also be used as a platform to compare candidates’ platforms and facilitate discussions.

It started off as a basic question: what if there was an easy way to put together profile pictures? It turned out to have social utility in a pivot from our existing platform. We followed those veins, and a few years later it’s now officially a profitable startup, with Lynbrook High being our first customer.

It’s a rough framework, but the most important part of it is that you have to be slightly embarrassed by the first version of an idea you put out. Pursue an interesting idea and don’t be afraid of the consequences.

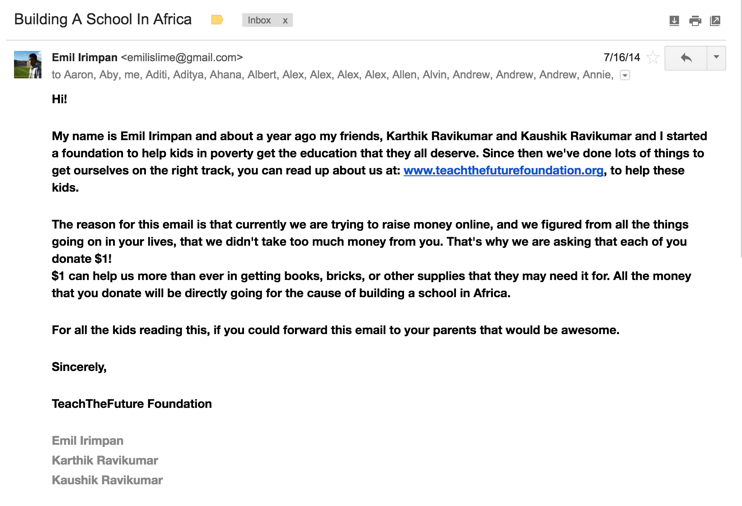

When my friends Karthik, Kaushik, and Emil started their non-profit Teach the Future Foundation, they wanted to do something big. They made shameless plugs to all their friends and family, went door to door, and offered free car washes at Jiffy Lubes. You’d never figure with emails like this, they’d be able to raise $70,000.

teachthefuturefoundation.weebly.com/

teachthefuturefoundation.weebly.com/

Yet four years later, they hit their goal and spent their summer building a school in Kenya that supports over 200 students.

We see this in real world companies too.

The Russians rejected Elon’s offer to buy an old spacecraft, so he started to ask if he could build a better one himself. He approached a slow moving space industry, learned what he needed to, and found a way to reuse shuttles.

Ray Dalio wondered if he could systemize investing to let computers do the thinking for him. He worked algorithms into Excel spreadsheets and looked for common principles. It became essential to growing the world’s largest hedge fund.

Kevin Systrom was interested in the idea of sharing locations and built Burbn, an app that allowed users to check in at locations and share plans with their friends. Yet, nobody was sharing their locations; they were using the app to share photos. He found utility amongst one of the various features, expanded it, and went on to rebrand as Instagram.

Sitting at opposite ends of one another, ego and curiosity are at a constant battle. At the expense of new perspectives, we avoid opportunities to save face. It’s natural — we’re afraid of being wrong, being disagreed with. It’s not easy to tread a path that no one else has taken. It’s why we need to think like second graders.

A second grader is fearless in asking questions and diving into them. Years of schooling, standardized testing, and educational standards teach us that we have to follow the traditional model to be successful. This is backwards: most groundbreaking inventions and ideas don’t come from commonly followed paths, or else they wouldn’t be groundbreaking.

Curiosity unearths important ideas that seem risky in foresight and obvious to us in retrospect — to see something in a space where nobody else sees it. That’s why you might look at an idea like Uber or Snapchat and wonder how you didn’t come up with it.

So, keep an open mind in areas that already interest you. Always ask questions. If an answer ever piques your interest, pursue it. Stick to it. Constantly measure its worth and never stop reiterating what isn’t working out. It doesn’t really matter if it fails or not, because it’s a side project. They’re meant to be just poking around the sand.

That’s how every project I’ve started has come to be. I can’t count the number of times I’ve just stumbled into “filler sand” and thrown out a project.

It’ll take a lot of dirty work. Some will dismiss your work as silly, nonessential, child’s play. You might be grasping at nothing at all. But if you can adopt the fearless curiosity of a second grader, then who knows. You might see something interesting. You might dig deeper. Eventually, you might just stumble onto platinum.